Why do we need new treatments for schizophrenia?

A valid question. After all, we’ve had anti-psychotic drugs for decades, haloperidol (Haldol) has been around since the 60s, and second generation atypical anti-psychotics such as olanzapine (Zyprexa) and risperidone (Risperdal) came around in the 70s and 80s. Since then we’ve just been making variations on a theme, with no new classes of drug being developed so far.

The current drugs are pretty effective in treating the so-called positive symptoms (a spectacularly inappropriate term that somehow stuck) of hallucinations and delusions. They do this by blocking signalling of a neurotransmitter called dopamine, which is increased in schizophrenia.

However, they don’t do anything about the so-called negative symptoms (far more appropriate term), which include things like apathy, emotional blunting, social problems and memory issues. These things aren’t caused by dopamine. What are they caused by? Good question. We know there are differences in brain structure in schizophrenia patients compared to neurotypical people. Some people look towards the immune system to explain this.

What happening with the immune system in schizophrenia?

Let’s start at the beginning; why did people think targeting microglia, the immune cells of the brain, was a good idea? There is a long history of research into the role of the immune system in schizophrenia. We know a significant risk factor for in individual to develop schizophrenia is for their mother to contract an infection during pregnancy. The thinking is that the immune response by the mother affects brain development of the foetus.

Other risk factors include severe and chronic stress during childhood, for instance being exposed to abuse, famine or warfare. This chronic stress also leads to immune system activation. Lastly, we’ve now characterised well over 150 genetic risk factors which increase the risk for schizophrenia. Many of these are also involved in the immune response.

This isn’t just theorising; a common finding in the blood or cerebrospinal fluid of schizophrenia sufferers is elevated levels of immune factors, suggesting their immune system is somehow over-active.

Over-active microglia in schizophrenia?

Ok, so looks like there is involvement of the immune system in schizophrenia. As I described here, the immune system in the brain is different from the rest of the body, the brain has its own special immune cells, the microglia. Obviously, the next logical step would be to look at if microglia in schizophrenia patients are more active. People have done this using brain scans with a (mildy) radioactive probe for microglia and found that, indeed, this is the case (see for instance here).

Overzealous microglia are bad news, as I described in the second section here. It is a reasonable assumption that, if there is excess microglia activity, this leads to loss of neuronal connections and altered neuronal functioning, and that this could underlie some of the symptoms. So, the obvious next step is to calm down the microglia.

How can we hit microglia?

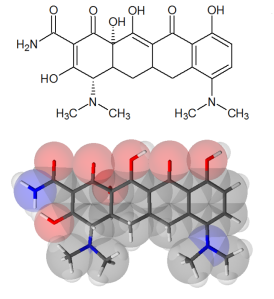

Ah, at least here there is a simple answer: minocycline. This was developed as an antibiotic, but along the line someone clever noticed it also inhibits the activity of microglia.

Actually, minocyline is quite a ‘dirty’ drug, it is not very specific. It does other things in the brain as well, but for the purposes of the things we’re looking at today, the microglia effects are the most important.

Well? Does it work?

Between 2010 and 2015 the initial studies on minocyline in schizophrenia were reported. The tally? Four showing beneficial effects (1, 2, 3 and 4), two showing no change (1 and 2) in schizophrenia symptoms.

A recent meta-analysis (collating several of the earlier small studies) found small positive effects that were borderline significant. Promising, but nothing to write home about. These early trials were followed by larger trials trying to confirm these effects. These are now reporting their findings.

The results of the latest mincocycline trial (BeneMin, one of the largest yet) were presented by Bill Deakin at last month’s British Association for Psychopharmacology Summer Meeting, see my tweet with some of his results here. Long story short, absolutely nothing happened. No effects whatsoever.

This was in direct contradiction to one of the earlier positive studies, led by Bill Deakin as well. So, this leaves us with a net score of 3 vs 3, with the three “winners” generally being close calls.

So why isn’t minocycline the silver bullet for schizophrenia?

Pick your poison:

- We’re not treating long enough

- We’re not treating early enough

- We’re not using the right drug

- We aren’t treating the right patients

- All microglia are not the same

- Microglia really don’t have anything to do with the disease

- All of the above (ie we have no idea what we’re doing)

The first two options are the most charitable interpretation of recent data. The reshaping of neuronal circuits and the other jobs they do can be slow processes, and it may take a long time for the drug to have enough of an effect in the brain to see a difference in symptoms.We would just need to treat for longer. It may also be that by the time symptoms are severe enough to need treatment, there are so many changes in the brain that just inhibiting microglia isn’t enough. You could think of treating people at high risk of developing the disease.

Are we using the right drug? Difficult question. Minocycline is just one option. People have tried other, more general, anti-inflammatory drugs such as NSAIDS, or immune suppressors like methotrexate, These drugs don’t target the microglia themselves, but the inflammatory process that activates them. So far, these trials have shown at most modest effects or less.

It may be that there are subtypes of schizophrenia and treating everyone in this way isn’t helpful. This concept is already being used in depression trials, where a distinction is being made between “inflammatory” and “non-inflammatory” patients. It might very well be the case that stratifying patients and targeting treatment that way could work in schizophrenia as well. I think this is likely (and also shows we still really don’t understand what is going on).

Maybe not all microglia are created equal. It’s known that there is a lot of diversity of microglia, in different brain regions, even between cells in the same region. Some may be more activated, and some may even be beneficial. Just shutting all of them down may be like taking a sledgehammer to a mosquito, and we should be targeting specific populations of cells. How that could be done is left as an exercise to the reader….

It could also be we’re barking up completely the wrong tree. Microglia are a logical and tempting target, given available data. But what about that data? For instance, the brain scans showing over-activation of microglia? Turns out the radioactive tracer used isn’t actually specific for microglia at all, and measures who knows what else as well. So are microglia actually more activated in schizophrenia sufferers? We don’t know for sure. The possibility still exists that microglia play no role at all, though I doubt that.

To be honest, the last option (“we have no idea what we’re doing”), is probably closest to the truth at the moment….

Where to go from here?

Well, walk before we run, I’d say. Scientists are people too, and we get excited as well. I think that when the data on raised inflammatory factors, and later the scans supposedly showing microglial over-activation, came through, people made the logical mental leap to start hitting microglia, without knowing what is actually going on (surprisingly common in trials, actually).

I think the (circumstantial) evidence that microglia are involved in schizophrenia is there, but we need to be cleverer in targeting them. Just hitting all of them clearly isn’t the answer. What do we need to hit and how to do it? More research required! (Get back to me in five years time…..)

Stay tuned for more posts here on Neuroscience Ramblings, and in the mean time, follow me on Twitter: @DrNielsHaan

2 thoughts on “Anti-microglial treatments in schizophrenia – why aren’t they going anywhere?”